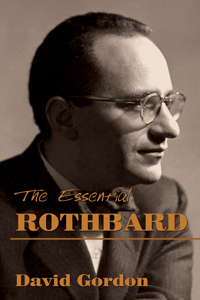

I have been reading several introductions by Joseph Salerno in books by Murray Rothbard. Both introductions are excellent in scope, explanation, and logic. In the segment below, Salerno introduces a concept that Ludwig Von Mises called Thymology – the study of human valuations. Each person is motivated to act by his or her assessment of value placed on alternative courses of action which is why history is not as predictable as the laws of nature. Nonetheless, entrepreneurship and leadership are impossible predictive capabilities of people actions, indicating the need for either a conscious or unconscious competence in thymology.

Mises and Rothbard have taken to the principles of thymology and used them in ascertaining the motives of historical movers and shakers. This, in my opinion, is one of Mises greatest breakthroughs, explaining why men and women behave in history the way they do through the study of what they valued as important. Ideas are the mainspring of all change and when men and women comprehend truth, world-sized change is possible. In contrast, however, when men and women are indoctrinated with lies, living a life of honor and nobility becomes increasingly difficult.

LIFE Leadership has a mission to transform lives through leading people to truth. We do so by building communities of people that Have Fun, Make Money, and Make a Difference by providing life-changing information in the 8F’s. We make a difference on life at a time and the study of thymology helps us understand where a person is at so we can help him get to where he wants to go.

Sincerely,

Orrin Woodward

Understanding the values and goals of others is thus an inescapable prerequisite for successful action. Now, the method that provides the individual planning action with information about the values and goals of other actors is essentially the same method employed by the historian who seeks knowledge of the values and goals of actors in bygone epochs. Mises emphasizes the universal application of this method by referring to the actor and the historian as “the historian of the future” and “the historian of the past,” respectively. Regardless of the purpose for which it is used, therefore, understanding aims at establishing the facts that men attach a definite meaning to the state of their environment, that they value this state and, motivated by these judgments of value, resort to definite means in order to preserve or to attain a definite state of affairs different from that which would prevail if they abstained from any purposeful reaction. Understanding deals with judgments of value, with the choice of ends and of the means resorted to for the attainment of these ends, and with the valuation of the outcome of actions per-formed.

Furthermore, whether directed toward planning action or interpreting history, the exercise of specific understanding is not an arbitrary or haphazard enterprise peculiar to each individual historian or actor; it is the product of a discipline that Mises calls “thymology,” which encompasses “knowledge of human valuations and volitions.” Mises characterizes this discipline as follows: Thymology is on the one hand an offshoot of introspection and on the other a precipitate of historical experience. It is what everybody learns from intercourse with his fellows. It is what a man knows about the way in which people value different conditions, about their wishes and desires and their plans to realize these wishes and desires. It is the knowledge of the social environment in which a man lives and acts or, with historians, of a foreign milieu about which he has learned by studying special sources.

Thus, Mises tells us, thymology can be classified as “a branch of history” since “[i]t derives its knowledge from historical experience.” Consequently, the epistemic product of thymo-logical experience is categorically different from the knowledge derived from experiments in the natural sciences. Experimental knowledge consists of “scientific facts” whose truth is independent of time. Thymological knowledge is confined to “historical facts,” which are unique and nonrepeatable events. Accordingly, Mises concludes,

All that thymology can tell us is that in the past definite men or groups of men were valuing and acting in a definite way. Whether they will in the future value and act in the same way remains uncertain. All that can be asserted about their future conduct is speculative anticipation of the future based on specific understanding of the historical branches of the sciences of human action. . . . What thymology achieves is the elaboration of a catalogue of human traits. It can moreover establish the fact that certain traits appeared in the past as a rule in connection with certain other traits.

More concretely, all our anticipations about how family members, friends, acquaintances, and strangers will react in particular situations are based on our accumulated thymological experience. That a spouse will appreciate a specific type of jewelry for her birthday, that a friend will enthusiastically endorse our plan to see a Clint Eastwood movie, that a particular student will complain about his grade—all these expectations are based on our direct experience of their past modes of valuing and acting. Even our expectations of how strangers will react in definite situations or what course political, social, and economic events will take are based on thymology. For example, our reservoir of thymological experience provides us with the knowledge that men are jealous of their wives. Thus, it allows us to “understand” and forecast that if a man makes overt advances to a married woman in the presence of her husband, he will almost certainly be rebuffed and runs a considerable risk of being punched in the nose.

Moreover, we may forecast with a high degree of certitude that both the Republican and the Democratic nominees will outpoll the Libertarian Party candidate in a forthcoming presidential election; that the price for commercial time during the televising of the Major League Soccer championship will not exceed the price for commercials during the broadcast of the Super Bowl next year; that the average price of a personal computer will be neither $1 million nor $10 in three months; and that the author of this paper will never be crowned king of England. All of these forecasts, and literally millions of others of a similar degree of certainty, are based on the specific understanding of the values and goals motivating millions of nameless actors.

As noted, the source of thymological experience is our interactions with and observations of other people. It is acquired either directly from observing our fellow men and transacting business with them or indirectly from reading and from hearsay, as well as out of our special experience acquired in previous contacts with the individuals or groups concerned. Such mundane experience is accessible to all who have reached the age of reason and forms the bedrock foundation for forecasting the future conduct of others whose actions will affect their plans. Furthermore, as Mises points out, the use of thymological knowledge in everyday affairs is straightforward:

Thymology tells no more than that man is driven by various innate instincts, various passions, and various ideas. The anticipating individual tries to set aside those factors that manifestly do not play any concrete role in the concrete case under consideration. Then he chooses among the remaining ones.

To aid in this task of narrowing down the goals and desires that are likely to motivate the behavior of particular individuals, we resort to the “thymological concept” of “human character. ” The concrete content of the “character” we attribute to a specific individual is based on our direct or indirect knowledge of his past behavior. In formulating our plans, “We assume that this character will not change if no special reasons interfere, and, going a step farther, we even try to foretell how definite changes in conditions will affect his reactions.” It is confidence in our spouse’s “character,” for example, that permits us to leave for work each morning secure in the knowledge that he or she will not suddenly disappear with the children and the family bank account. And our saving and investment plans involve an image of Alan Greenspan’s character that is based on our direct or indirect knowledge of his past actions and utterances. In formulating our intertemporal consumption plans, we are thus led to completely discount or assign a very low likelihood to the possibility that he will either deliberately orchestrate a 10-percent deflation of the money supply or attempt to peg the short-run interest rate at zero percent in the foreseeable future.

While thymology powerfully, but implicitly, shapes everyone’s understanding of and planning for the future in every facet of life, the thymological method is used deliberately and rigorously by the historian who seeks a specific understanding of the motives underlying the value judgments and choices of the actors whom he judges to have been central to the specific event or epoch he is interested in explaining. Like future events and situations envisioned in the plans of actors, all historical events and the epochs they define are unique and complex outcomes codetermined by numerous human actions and reactions. This is the meaning of Mises’s statement.

History is a sequence of changes. Every historical situation has its individuality, its own characteristics that distinguish it from any other situation. The stream of history never returns to a previously occupied point. History is not repetitious.

It is precisely because history does not repeat itself that thymological experience does not yield certain knowledge of the cause of historical events in the same way as experimentation in the natural sciences. Thus the historian, like the actor, must resort to specific understanding when enumerating the various motives and actions that bear a causal relation to the event in question and when assigning each action’s contribution to the outcome a relative weight. In this task, “Understanding is in the realm of history the equivalent, as it were, of quantitative analysis and measurement.” The historian uses specific understanding to try to gauge the causal “relevance” of each factor to the outcome. But such assessments of relevance do not take the form of objective measurements calculable by statistical techniques; they are expressed in the form of subjective “judgments of relevance” based on thymology. Successful entrepreneurs tend to be those who consistently formulate a superior understanding of the likelihood of future events based on thymology.