Murray Rothbard is my favorite economist to read for several reasons. First, his extensive knowledge in economics, history, and business help him see connections where few others would. Second, his style of writing drives home his points in an enjoyable fashion and, even the few times where I believe he goes too far, I still marvel at his ability to muster the facts in a logical fashion to argue his point. to

As Chairman of the Board for LIFE Leadership, I am constantly reading, writing, and speaking. Identifying the top thinkers to read in each field is a high-priority for me and why Murray Rothbard is one of my favorites. For his thinking and writing clear the fog of ignorance on my different subjects. As an example, here is Rothbard’s description of how and why America cartelized its corporations in the late 19th century.

The Five Laws of Decline are alive and well in America and a return to the Six Duties of Society is going to take an active group of people who know leadership, history, and economics.

Sincerely,

By the late 19th century, the Morgans took the lead in trying to pressure the US government to cartelize industries they were interested in — first railroads and then manufacturing: to protect these industries from the winds of free competition, and to use the power of government to enable these industries to restrict production and raise prices.

In particular, the investment bankers acted as a ginger group to work for the cartelization of commercial banks. To some extent, commercial bankers lend out their own capital and money acquired by CDs. But most commercial banking is “deposit banking” based on a gigantic scam: the idea, which most depositors believe, that their money is down at the bank, ready to be redeemed in cash at any time. If Jim has a checking account of $1,000 at a local bank, Jim knows that this is a “demand deposit,” that is, that the bank pledges to pay him $1,000 in cash, on demand, anytime he wishes to “get his money out.” Naturally, the Jims of this world are convinced that their money is safely there, in the bank, for them to take out at any time. Hence, they think of their checking account as equivalent to a warehouse receipt. If they put a chair in a warehouse before going on a trip, they expect to get the chair back whenever they present the receipt. Unfortunately, while banks depend on the warehouse analogy, the depositors are systematically deluded. Their money ain’t there.

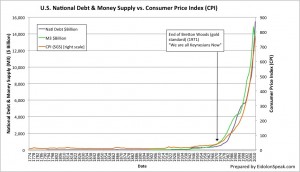

An honest warehouse makes sure that the goods entrusted to its care are there, in its storeroom or vault. But banks operate very differently, at least since the days of such deposit banks as the Banks of Amsterdam and Hamburg in the 17th century, which indeed acted as warehouses and backed all of their receipts fully by the assets deposited, e.g., gold and silver. This honest deposit or “giro” banking is called “100 percent reserve” banking. Ever since, banks have habitually created warehouse receipts (originally bank notes and now deposits) out of thin air. Essentially, they are counterfeiters of fake warehouse receipts to cash or standard money, which circulate as if they were genuine, fully backed notes or checking accounts. Banks make money by literally creating money out of thin air, nowadays exclusively deposits rather than bank notes. This sort of swindling or counterfeiting is dignified by the term “fractional reserve banking,” which means that bank deposits are backed by only a small fraction of the cash they promise to have at hand and redeem. (Right now, in the United States, this minimum fraction is fixed by the Federal Reserve System at 10 percent.)

Fractional Reserve Banking

Let’s see how the fractional-reserve process works, in the absence of a central bank. I set up a Rothbard Bank, and invest $1,000 of cash (whether gold or government paper does not matter here). Then I “lend out” $10,000 to someone, either for consumer spending or to invest in his business. How can I “lend out” far more than I have? Ahh, that’s the magic of the “fraction” in the fractional reserve. I simply open up a checking account of $10,000 which I am happy to lend to Mr. Jones. Why does Jones borrow from me? Well, for one thing, I can charge a lower rate of interest than savers would. I don’t have to save up the money myself, but can simply counterfeit it out of thin air. (In the 19th century, I would have been able to issue bank notes, but the Federal Reserve now monopolizes note issues.) Since demand deposits at the Rothbard Bank function as equivalent to cash, the nation’s money supply has just, by magic, increased by $10,000. The inflationary, counterfeiting process is under way.

“Unfortunately, while banks depend on the warehouse analogy, the depositors are systematically deluded. Their money ain’t there.”

The 19th-century English economist Thomas Tooke correctly stated that “free trade in banking is tantamount to free trade in swindling.” But under freedom, and without government support, there are some severe hitches in this counterfeiting process, or in what has been termed “free banking.”

First, why should anyone trust me? Why should anyone accept the checking deposits of the Rothbard Bank?

But second, even if I were trusted, and I were able to con my way into the trust of the gullible, there is another severe problem, caused by the fact that the banking system is competitive, with free entry into the field. After all, the Rothbard Bank is limited in its clientele. After Jones borrows checking deposits from me, he is going to spend that money. Why else pay for a loan? Sooner or later, the money he spends, whether for a vacation, or for expanding his business, will be spent on the goods or services of clients of some other bank, say the Rockwell Bank. The Rockwell Bank is not particularly interested in holding checking accounts on my bank; it wants reserves so that it can pyramid its own counterfeiting on top of cash reserves. And so if, to make the case simple, the Rockwell Bank gets a $10,000 check on the Rothbard Bank, it is going to demand cash so that it can do some inflationary counterfeit pyramiding of its own.

But, I, of course, can’t pay the $10,000, so I’m finished. Bankrupt. Found out. By rights, I should be in jail as an embezzler, but at least my phoney checking deposits and I are out of the game, and out of the money supply.

Hence, under free competition, and without government support and enforcement, there will only be limited scope for fractional-reserve counterfeiting. Banks could form cartels to prop each other up, but generally cartels on the market don’t work well without government enforcement, without the government cracking down on competitors who insist on busting the cartel, in this case, forcing competing banks to pay up.